If you’re a coffee lover, there might be no better smell than the early-morning aroma of fresh java diffusing through your home. Depending on your preference, that smell—and the coffee’s taste—could be nutty, smooth, or sweet.

Those flavors are analyzed through coffee cupping, “a globally standardized method for evaluating the qualities of a coffee,” according to Methodical Coffee. “It’s a method used for the evaluation of coffee but also used as quality control to ensure a coffee roast is tasting as great as it can be.” A coffee flavor wheel provides language to describe the taste of various coffees, whether delicate or heavy, fruity, or nutty.

In the same way, sensory experiences of soil can be captured through smell tests.

The Idea Percolates

Finn Woodings, Ph.D. student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and coffee enthusiast, applies the principles of flavor wheels and coffee cupping to soil science.

Neuroscience, which he studied for undergrad, motivated him to analyze how smell contributes to a farmer’s understanding of soil.

“Farmers have this working knowledge from decades of managing their soils,” he says.

And this working knowledge, especially knowledge captured through farmers’ sensory experiences during fieldwork, could contribute to how farmers perceive the health of their soils, Woodings hypothesizes.

This idea began percolating during a field day conversation between Woodings and his colleague Luke Bergschneider, a farmer who also works in Extension for the Margenot Soils lab.

“He mentioned how you can smell the difference in soil,” Woodings says. “He said, ‘You can smell that this one is a good soil. You can smell this soil is going to grow more corn and has more organic matter than this other soil.’”

When Woodings investigated this concept, he found YouTube videos of soil smell test demonstrations from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and collaborative research from the early ’90s between farmers and researchers in Illinois and Wisconsin.

“When the importance of soil health was emerging in research, there was some work done together with farmers and researchers where they would go out and they would measure all of the physical, chemical, and biological properties of a soil,” Woodings says. “They would also include some metrics that were sensory based. So they would have the farmers rate the soil based on what it looked like, what it felt like, and what it smelled like.”

The core idea was to capture biological aspects of soils beyond chemical fertility status. But, Woodings adds, the biggest critique on using sensory indicators is their subjectivity.

“It’s not usually objective, but in food sciences and marketing, sensory work is critical,” Woodings says. “They’ve developed methods where you can use somebody’s nose or taste buds to evaluate different sensory features of food in a standardized and objective way.”

Smell Test Prep

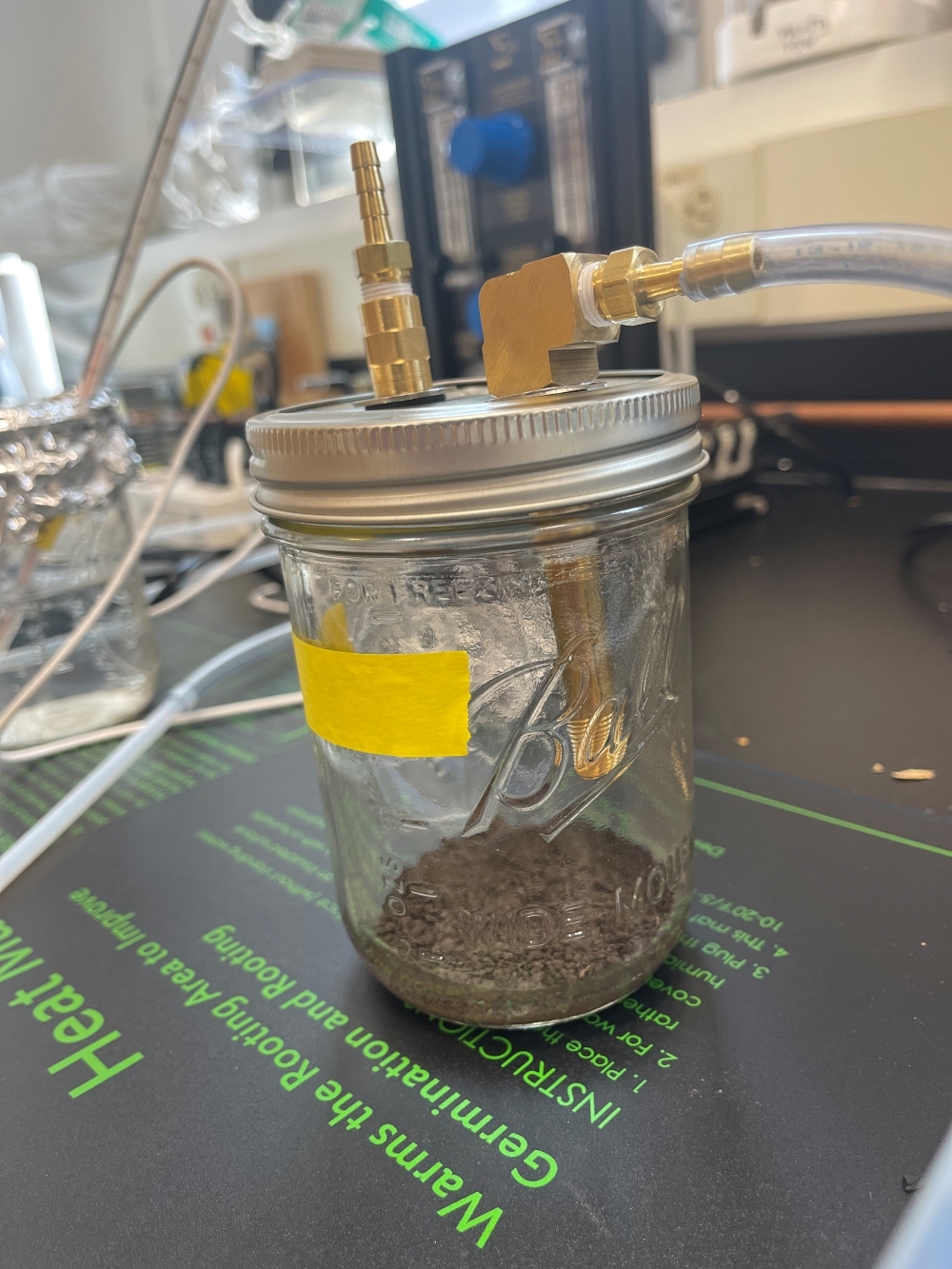

To leverage those food science methods, Woodings worked with Dr. Yanina Pepino, a sensory scientist in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition at the University of Illinois. Together, they used smell tests, a way to evaluate a sample by odor, to test the hypothesis that farmers can smell soil health.

“Odor is a really interesting sense in that a lot of your olfaction is subconscious,” Woodings says. “Our brains have a huge capacity to smell, to recognize odors, and to make decisions based on that odor.”

To prepare for the sensory tests, Woodings and his team analyzed soil samples collected by the Diverse Corn Belt Project’s In-Field Team to find soils with low, medium, or high soil health across Illinois and Indiana.

Woodings says there are several ways to define soil health, which can provide a challenge in the research community. This challenge of quantifying soil health is, in part, what spurred the idea to quantify soil health from a farmer’s perspective. His team chose a combination of management-based and NRCS indicator-based definitions.

“A grazed perennial system is thought to embody soil health principles in these agroecosystems,” he says. “You’re putting living roots in the soil. You’re covering it year-round. You’re often adding as much diversity as possible with diverse mixes and grazing livestock. You’re minimizing disturbance.”

A medium soil health sample could come from a field where soils had been under cover crops and the field had been no-tilled for at least 10 years. Low implementation of soil health principles could be represented by fields with full-width tillage without cover crops.

But field management is only one part of soil health, Woodings notes. Context also matters.

So he and his team measured the samples’ biological parameters, including microbial biomass, organic matter, and mineralization. Where the management-based definition converged with the biological indicator scores, the soils were designated as “low,” “medium,” or “high,” relative to each other.

“Our brains have a huge capacity to smell, to recognize odors, and to make decisions based on that odor.”

In the university’s food sensory lab, 10 Illinois farmers were given 18 rounds of soil samples with no indication of their soil health designations. Each round contained three samples for the farmers to smell and respond to, ranking the soils in order of what they perceived as healthy soil.

“We didn’t provide them an odor-based definition beyond the NRCS-based definition of soil health, which essentially captures the ability of soil to sustain function to support plant and animal life,” Woodings says. “We simply wanted their intuitive response as to, ‘What do you think smells like soil health?’”

Farmers could write comments on the samples, explaining their thoughts on the character of the soils or how two samples might smell similar.

“We had one farmer who would say that a soil smelled really tasty when they perceived it as healthy,” Woodings says. “‘Made their mouth water,’ I believe was exactly how they said it.”

After the smell test, producers and the research team brewed language to describe specific soil odors, similar to the creation of the coffee flavor wheel. Woodings worked with a French company, Éditions Jean Lenoir, to obtain reference smells, which provided a starting point for the group.

Through conversation with the farmers, they crafted phrases like “musty, stale, earthy” to convey an unpleasant smell (like water sitting in a basement) and “fresh, damp, earthy” to characterize a pleasant soil smell (like living worms or compost).

“We didn’t expect to assign odors as ‘pleasant’ or unpleasant,’” Woodings says, “but the farmers felt this was important for discriminating these types of earthy odors.

“It takes intentional cultivation of language to figure out what it is about the soil odor that led the farmer to think a soil was healthy or unhealthy by smelling. It could be that farmers smell soil from different fields, and they know the words to capture the difference, but they can’t quite put their finger on it. This is common with odor because of how it’s processed by the brain. That list of the odor attributes we’ve developed is an important tool for farmers to have.”

“We had one farmer who would say that a soil smelled really tasty when they perceived it as healthy.”

Applying “Scent Detective Work” for Soil Management

With the olfactory sense’s close relationship with emotions, learning, and memory, Woodings says smell may play a role in informing how farmers perceive management to impact their soils.

“Farmers may have picked up on the cues and they’ve learned, ‘Okay, this is what healthy soil smells like, this is what one that needs a little bit more work smells like,’” Woodings says. “‘Maybe I should think about implementing some cover crops in this field, or maybe my fertility is off.”

Woodings also works with Dr. Esther Ngumbi, a chemical ecologist in the entomology department at the University of Illinois, on “scent detective work” to identity the compounds responsible for the odors in soil.

“We have a lot of work to do in order to tie these things together and figure out how the chemicals causing the odors are reflecting what’s going on in the soil,” Woodings says.

Soil smell research can be a “powerful education tool,” he notes.

“The soil health concept in general has this analog to human health that allows us to understand it more easily,” he says. “We understand human health; we understand the concept of going to the doctor and getting a check-up and making sure that everything is in working order and that we need to change how we are managing our bodies to be healthier, whatever that looks like for an individual.”

But, he adds, the meaning of health can seem more vague when we think about soils. Woodings’ Ph.D. work focuses on improving how we quantify soil health.

“It can be difficult to understand, what is a healthy soil and what does that mean,” Woodings says. “If we can integrate a sensory experience like odor into that education, it can be a really powerful tool. A healthier soil, it holds more water, it recycles nutrients and provisions plants and does all these positive things for ecosystem health overall. We can say these things, but here, you can smell it. That can be powerful.”

Learn more about the soil health work of the DCB In-Field Team in The Dimensions of Soil Health: Measuring Soil Properties in the Field.