The notion of diversification is nothing new to farming, but taking the initial steps forward is both unfamiliar and risky. The Diverse Corn Belt Modeling Team is building a case for diversification by examining food production as it currently exists and what it could look like moving forward. A key step: Modeling foodsheds.

Dr. David Mulla, Professor and Larson Chair for Soil & Water Resources in the Department of Soil, Water, and Climate at the University of Minnesota, sees a bright future for foodsheds. There is big potential for changing where big cities source food and what kind of diets citizens eat, with positive repercussions on the landscape of the Midwestern U.S. He is currently serving on the DCB Modeling Team.

Instead of the majority of Midwestern land planted to row crops, with harvests destined to feed animals or to produce biofuels, “we could envision a totally different landscape where we’re growing food for the local humans to eat,” Mulla says, “And I think the natural resources of the farm itself would improve, especially soil health. There would be better aggregate stability, better infiltration, higher organic matter contents on fields, and just better soil health.”

“We could envision a totally different landscape where we’re growing food for the local humans to eat.”

The Modeling Exercise

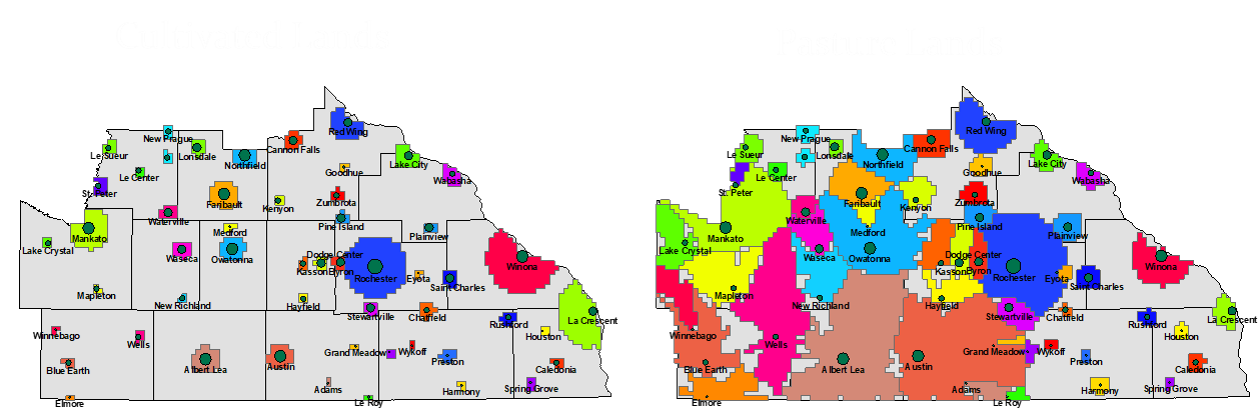

Understanding and actively addressing the food needs of the Midwest and applying that to the requirements of the local foodshed is the core work of the DCB Modeling Team.

“We’re relying on surveys that have been done by other DCB teams,” Mulla says. “Surveys of farmers, of wholesalers, and of retailers to find out what is being grown, where it is being grown, where it is being purchased, and other details of the food production chain.”

Similar to the more well-known term “watershed,” a foodshed is defined as the “geographical area between where food is produced and where the food is consumed,” according to Michigan State University Extension.

“You can think of foodsheds in terms of locality,” Mulla says. “For instance, all the areas where a municipality or village could obtain all the meat, milk, fruits, and vegetables that are needed for daily caloric intake.”

A key difference from a watershed is that foodsheds can differ in size and character depending on what can be grown practically or economically in a region and also vary depending on local tastes.

“We can source chocolate from Africa, for example, and bananas from South America, which is part of an international foodshed, but we should not be sourcing foods we can grow in our local foodshed from those places,” Mulla says. “The idea of our work is to bring food production to the local area and, as much as possible, try to cut off our need to grow food in faraway places where transportation and processing come into play.”

To pull the foodshed model together, the Modeling Team identifies what can be grown in an area, and a certain amount of that food is assigned to daily diets of the local consumers.

“There could be some real benefits economically to communities and to the environment in terms of efficient water use, reduced erosion, and reduced air pollution,” Mulla says.

Locally focused foodsheds will work with businesses that support production and transportation of food and use the area’s workforce. And it puts money back into the communities.

“Rather than paying a large multinational corporation that might be based in another country, that money would flow back into communities to revitalize main streets and downtown areas and create a better tax base for education,” Mulla says. “We could be doing a lot better than we are in terms of supporting the things we value in our own communities.”

Ultimately, Mulla estimates that it would take converting about 20% of the dedicated row crop planting by Corn Belt farmers to a more diverse crop rotation to create the economic and environmental benefits that are envisioned.

Beyond the five systems DCB focuses on, there are real market pressures that could drive this diversification movement.

“For example, if subsidies for the 40% of land currently planted for ethanol would be reduced, there would be incentive to look at other crop opportunities,” Mulla says. “There’s also increasing demand for plant protein options, TMDL reduction goals, and the desire to meet international standards for emissions of trace gases. Each factor provides a potential path to a more diverse foodshed.”

“If we shift that alfalfa production to the Midwest or create grazing operations for the animals, we hold soil down and reduce overall nitrogen use.”

Consumers: Embracing The Local Mindset

Standing in the way of planting that 20% to diverse crop acres are some practical hurdles, including labor availability to grow fruits and vegetables and limited options for crop insurance and subsidies.

And there’s the challenge of encouraging community members to think more about where their food comes from and to understand the implications of their dietary choices as they relate to local food.

“For example, if you’re eating meat that’s grown on a concentrated feeding operation, where alfalfa is grown in another state and shipped to the Midwest, that’s not benefitting local communities,” Mulla says. “Conversely, if we shift that alfalfa production to the Midwest or create grazing operations for the animals, we hold soil down and reduce overall nitrogen use.”

There’s also the consideration of the protein source itself, which doesn’t necessarily need to all come from animal production. Mulla notes that protein can be obtained from pulses and lentils like beans and edible peas that can be sourced locally, providing more options for consumers interested in alternative protein sources.

Farmers interested in being proactive about diversifying the foodshed can connect with food co-ops and restaurants in their area that focus on sourcing locally grown foods, he notes.

“There are a lot of those around, and if you do direct food-to-restaurant marketing that is a real golden pipeline,” Mulla says. “You can charge a premium for what you produce while performing a valuable service for your community.”

This article was written by veteran agriculture journalist Paul Schrimpf, president of Alameda Communications, and edited by DCB Communications Team Member Elise Koning, project director for Conservation Technology Information Center.