If you ask 100 farmers why they raise corn and soybeans, you will receive 100 different answers.

“There isn’t a single motivation that’s driving everybody,” DCB Team member Michael Tiboris says. “It’s really easy to look at the landscape, the homogeneity in the landscape, and assume that people’s motivations are similarly homogeneous, but that’s not true.”

Tiboris serves as policy director for the River Alliance of Wisconsin. As a philosopher, he has worked internationally on water politics and policy, food security, and smallholder farmer development. Currently, he collaborates with U.S. farmers on water quality and practice change.

“You can’t have functional policy that has a completely wrong view of people’s intuitions about what they’re doing.”

He says the role of philosophy in the Diverse Corn Belt Project (DCB) is to examine fair, just, or appropriate ways to approach change.

“Ultimately, you have to provide some account or justification for who’s going to win and who’s going to lose in that future scenario; you also might have to ask some difficult questions about how the burdens of transition operate,” Tiboris says.

The ethical principles of well-being, justice, and sustainability guide these questions. Well-being analyzes one’s experiences and how those experiences affect happiness and health. Justice examines fair distribution of burdens and how that distribution is justified. Sustainability considers an activity’s long-term value.

Questions asked throughout DCB examine why diversified agriculture should be adopted, as well as the justification for asking people to change what they do or how they see what’s important to them.

“Fundamentally, these questions aren’t answerable by just studying the facts of the case deeply,” Tiboris says. “We have to provide reasons and justification for why burdens fall where they fall. We tend to assume that agricultural diversity is a good thing, but that’s not universally accepted.”

Questions asked by the DCB Team include:

-

- “Why should we diversify?”

- “Why do we care about the values associated with diversifying, such as ecosystem health, farm resilience, and food security?”

- “Why should we believe those reasons are better than yield or productivity?”

- “What is the cost to transition from the current system to a diversified system?”

- “Who ought to bear the burdens and costs of the transition from one system to another?

- “Who should change their behavior so that we can have a diversified agriculture system?”

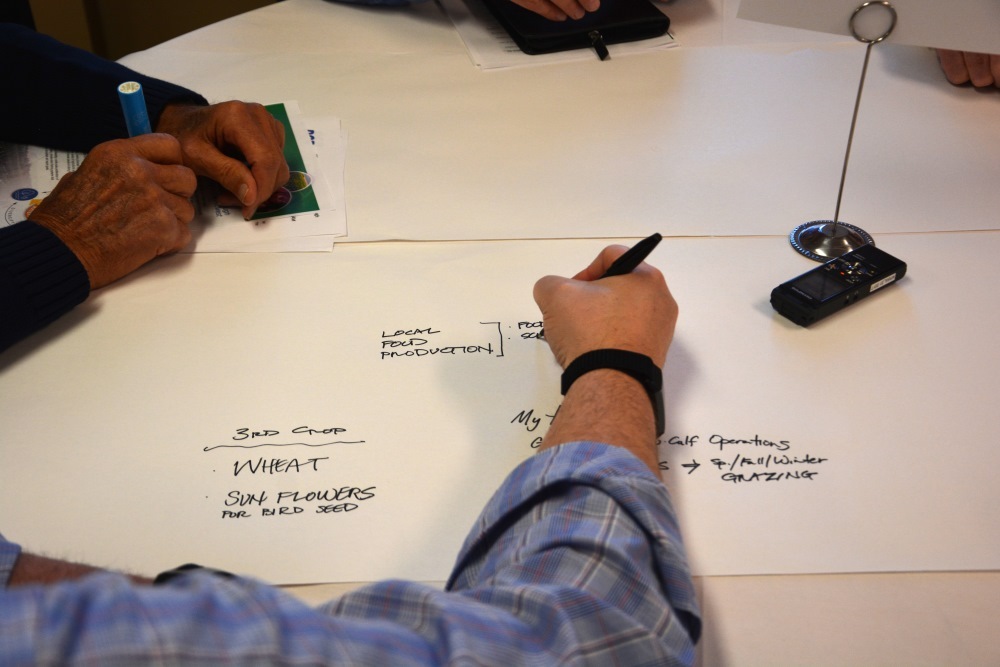

During RAD Team visioning sessions, DCB Team members seek to understand stakeholders’ views, goals, and beliefs.

“We want to know what people think, and we want to know what they value and why they value it,” Tiboris says.

Family legacy, religious commitments, yield, money, land stewardship, and a plethora of other motivations drive actions, Tiboris says. Sometimes, researchers’ and the general public’s views of what rural residents value differ from the residents’ actual values.

“Comparing our intuitions about what we think we would value if we were living in those places to what people who are actually operating in that space value and care about is super important for saying anything that’s going to be convincing to them, take them seriously, or be functional policy,” Tiboris says.

Understanding people’s motivations is essential when crafting policy, he adds.

“You can’t have functional policy that has a completely wrong view of people’s intuitions about what they’re doing,” Tiboris says. “It doesn’t work.”

“It’s a real cost to somebody to change the way that they see the world and the way they see themselves in order to move to a production system that’s going to have long-term benefits for lots of other people that are not them.”

For example, the costs of a transition will be borne by someone, whether a farmer, rural residents, specific demographic groups, or businesses, when transitioning to farms, markets, and landscapes with greater agricultural diversification. Even if all of society agreed that moving to a more diverse system is critical, one party will still bear the costs while another reaps the benefits.

“Especially in cases where there’s a cost to someone to make that change, we have to be able to make the argument in a way that people generally accept as convincing and compelling,” Tiboris says.

Tiboris says that agricultural diversity can make agriculture more resilient to change, improve ecosystem services, and positively affect public health. These benefits can be seen over a longer period of time for a greater number of people but might not be seen in the short term as an individual farmer.

“Farmers think about the work that they’re doing on the land, whatever system they’re using, as not just a practical activity, but one that expresses the kind of person that they are,” Tiboris says. “If you say they ought to change it, you’re saying something about them at a pretty personal level. It’s a real cost to somebody to change the way that they see the world and the way they see themselves in order to move to a production system that’s going to have long-term benefits for lots of other people that are not them.

“If you want to see more agricultural diversity on the landscape, it’s not enough to show them the finances and the water quality benefits or the landscape change benefits. Ultimately, that’s not enough to motivate a human being to do anything. It’s necessary, but not sufficient, as philosophers like to say.”

Learn more about asking questions through the RAD Team and the foundation of DCB in the blog post “Farmer Focus Groups: The Foundation of the DCB Project.”

This article was written by DCB Communications Team Member Elise Koning, project director for the Conservation Technology Information Center.