Creating a system where all farmers can succeed is part of the challenge of agricultural diversification. The Diverse Corn Belt Project is researching how diversifying the Corn Belt can work for everyone.

Systems thinking is a good place to start.

Natalie Hunt, a teaching assistant professor in Bioproducts & Biosystems Engineering at the University of Minnesota, says systems thinking affects not only farm products grown and marketed but also the people living and working on the land.

“Systems thinking is a critical tool to having a more sustainable and diverse workforce,” Hunt says. “We want an agricultural workforce to grow, and we want it to be more diverse, and we want it to be resilient.”

Hunt is part of the DCB Education Team, which is working to help students understand the challenges and opportunities of agricultural diversification in the Midwest.

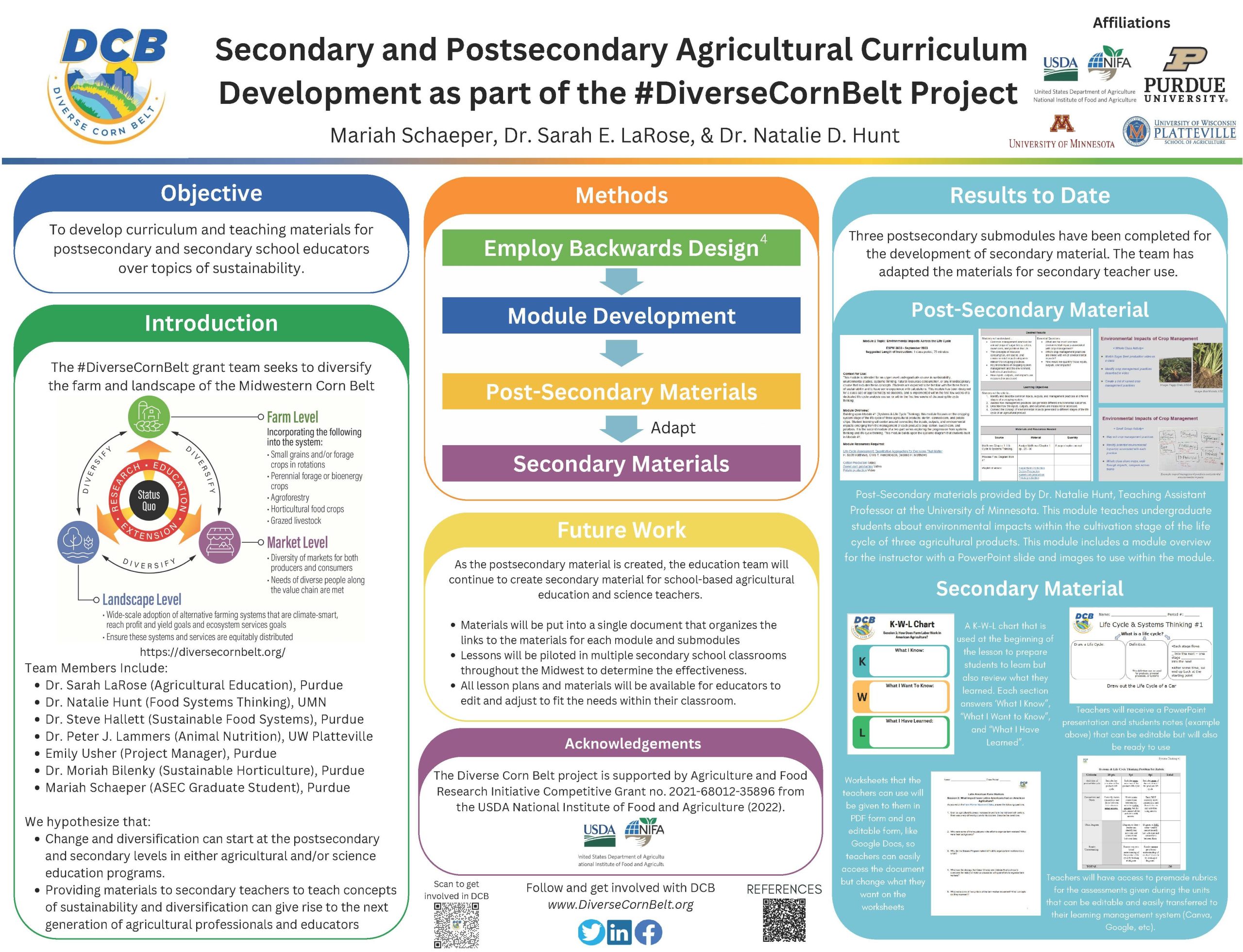

The Education Team within DCB is shaping educational modules that will help students learn about systems thinking as it relates to food systems. The modules are adapted for high school, college, and university courses. Instructors can pick and choose the modules they want to use for their courses.

Pete Lammers, Associate Professor of Animal, Dairy and Veterinary Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, says the modules are flexible, depending on what the teacher needs.

“The educational modules that we’ll be offering can be used as a complete set for a class on diversifying agriculture in the Corn Belt, as individual lectures, or as week-long topic discussions for existing courses,” Lammers says.

Lammers works with Hunt, Steve Hallett, professor of agriculture and co-founder of the Purdue University Student Farm, and Emily DeaKyne, DCB Project Manager, to write curriculum for post-secondary or university instructors.

“We want an agricultural workforce to grow, and we want it to be more diverse, and we want it to be resilient.”

The goal is to demonstrate how diversification adds resiliency to a farm, marketplace, or landscape. Each module focuses on one of four diversification areas: ecological, human, agricultural, or economic. Topics include the U.S. food system, migrant labor, the effect of species diversity on ecosystem function, and diverse agricultural systems, such as small grains, agroforestry, livestock, and food crops.

Sarah LaRose, associate professor of agricultural education at Purdue University, and her graduate student, Mariah Schaeper, adapt the curriculum from the post-secondary to the secondary level for high school students and teachers. The high school curriculum contains learning activities spread across five days of instruction for 50-minute lessons.

LaRose says the high school lessons are aligned with National Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources content standards.

“What we’re creating isn’t required curriculum,” LaRose says. “It’s an educational resource. We’re envisioning it as an à la carte buffet: take what you need. If you want to use all of it, you absolutely could.”

Hallett says the curriculum “bridges a gap,” not only in providing students information about agricultural diversification, but also in bridging the gap between education in sustainability and education in agriculture.

“When people generally talk about sustainability, they don’t talk about agriculture,” Hallett says.

Hunt says as a teacher, she noticed her sustainability and environmental studies students didn’t always understand agricultural systems.

“We build these bridging modules so that we’re teaching sustainability students to have some working knowledge of agricultural systems,” Hunt says. She adds there also is content for agriculture students on sustainability.

As they write the curriculum, the Education Team’s goal isn’t to teach students what to think—it’s to teach students how to think.

Along with the modules focused on the agriculture industry, the team has included modules on critical thinking. These resources focus on systems thinking, changing minds, and sustainability principles.

LaRose says the DCB curriculum will add valuable resources for teachers who don’t always have the tools they need.

“Teachers who work in public schools are continuously underfunded and not given the resources they need to be successful,” LaRose says.

Often, agriculture teachers instruct six or seven different courses in one day, jumping from horticulture to food science to ag business.

“Often, they don’t have textbooks or curriculum materials provided to them, so they’re trying to come up with it from scratch,” LaRose says. “There’s always a need for curriculum materials for high school educators.”

Lammers agrees.

“We want students who learn about this content to make change in their communities.”

“The individual classrooms are going to be very different in what resources they have access to and what and where the audience is coming from,” Lammers says. “You’re going to have to start the conversation where your audience is.”

Hallett says enabling students to understand historical, ecological, and human contexts of diversity enables them to enrich our Midwestern communities.

“Diversity is central, affects everything, and makes everything better, more beautiful, richer, more resilient,” says Hallett. “We really need to be understanding at a deeper level the historical context, all the different ecological and human contexts.”

LaRose says it’s about the students.

“We want students who learn about this content to make change in their communities because that’s the whole point of us doing the work: to make change so the Midwest can be a more resilient agricultural system for years to come,” LaRose says.